The Wiki for Tale 5 is in read-only mode and is available for archival and reference purposes only. Please visit the current Tale 11 Wiki in the meantime.

If you have any issues with this Wiki, please post in #wiki-editing on Discord or contact Brad in-game.

Difference between revisions of "Yeast Testing"

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

| − | + | == Isolating a Yeast == | |

| + | Once you have a location where a yeast you like predominates, your next responsibility is to determine a time to seal the kettle to let in only that yeast. This is sometimes called '''isolating''' the yeast. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The reason for isolating yeasts is that when making beer, the brew is (or, at least, can be) affected by all of the microbes that go into it. Having mold, acetobacter, or lactobacilli affecting your brew could ruin it completely, and at the very least will siphon off sugar that could be used to make precious, precious alcohol. On the other hand, having two or more different yeasts coexist in a brew isn't necessarily bad -- very often, it's good and desirable -- but predicting the results of single-yeast brews is a lot simpler. So it's typical for many brewers to just work with one yeast at a time. | ||

{| border="5" style="background-color:#f6dfb4;" | {| border="5" style="background-color:#f6dfb4;" | ||

| Line 46: | Line 49: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

You isolate a yeast by running a '''Yeast Test'''. This kettle option is a shortcut that eliminates the brewing phase, thus taking only 40 minutes to complete. At the end of the test, you take the 'beer' (you need your small barrel!) and get a display of the results. At the bottom is a list of the microbes that are in the kettle, in the order they entered (first to last). | You isolate a yeast by running a '''Yeast Test'''. This kettle option is a shortcut that eliminates the brewing phase, thus taking only 40 minutes to complete. At the end of the test, you take the 'beer' (you need your small barrel!) and get a display of the results. At the bottom is a list of the microbes that are in the kettle, in the order they entered (first to last). | ||

Revision as of 15:53, 11 March 2011

Yeast testing is a function of beer brewing, using the "Yeast Test" option on the Beer Kettle. It is used to determine the distribution of microbes at the kettle location. The overall goal of yeast testing is to find a location where the first microbe to enter the kettle is a yeast, and then (usually) to discover a seal time at that location where only that yeast (or that yeast along with other yeasts) gets in.

Introduction

To brew beer, you need to harness the power of one or more yeasts, which proliferate throughout Egypt. A kettle without yeast produces no alcohol -- and a brew without alcohol is nothing but shameful, undrinkable soup. Thus, before you make any real beer, you must locate a place for your kettle where a yeast can do its work. Once you have a suitable yeast spot, you also need to know the proper moment during fermentation to seal the kettle, to ensure that your brew contains only useful microbes (i.e. yeasts) and no harmful ones (everything else, generally). The process of determining these important variables is called yeast testing (sometimes called "petri-dishing" by our Tale 1 forebears).

Yeast testing is a hit-or-miss process and can be very time-consuming, but the good news is that you don't need a single drop of honey or grain of malt to do it. You just need the 60 wood and 25 water required to start your kettle -- plus about 40 minutes to do the test itself. Of course, the more beer kettles you own, the more testing you can do simultaneously.

Doing a Yeast Test

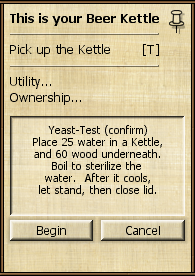

First, set down a Beer Kettle at the location you want to test (either by building one, or by dropping a Beer Kettle Kit in your inventory). Then choose the Yeast Test recipe from the interface window. As always when using a Beer Kettle, you will need 60 wood and 25 water to get it started.

The Yeast Test option is exactly like making a beer, except the brewing phase is omitted. Instead, the process starts right in with the 2400-second fermentation phase, which is when microbes begin entering the kettle. (You could also do a yeast test by choosing the Beer option, and then adding no ingredients during the brewing phase. It would be functionally the same thing. But it would also tack on an additional 20 minutes or so, to no purpose.)

During the fermentation phase, your only possible input (which is optional) is to seal the kettle. This prevents any further microbes from entering your kettle. Since your initial goal is to get as complete a list as possible of the microbes in your kettle, you shouldn't seal the first time you do a test at a location. Just leave the kettle running and come back in 40 minutes.

As always when using a Beer Kettle, you need a small barrel in your inventory to check your results -- whether you're making a beer or just testing microbes.

Checking Your Results

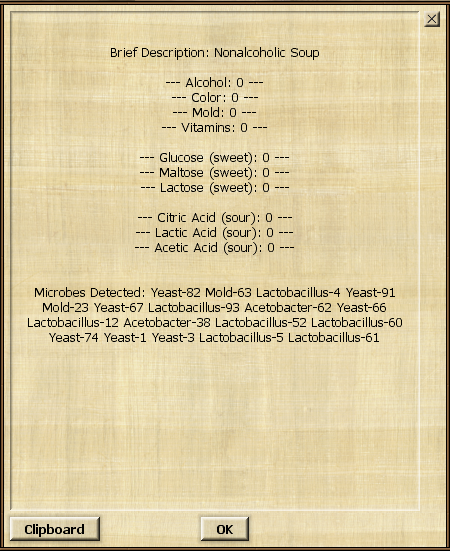

After the 2400-second fermentation phase is finished, you can view the results of your test. These will look very much like the picture to your left. Because you added no ingredients, your brew will not have alcohol or any other characteristics. The only relevant information -- and all that you are interested in -- is the list of "Microbes Detected" at the end.

Isolating a Yeast

Once you have a location where a yeast you like predominates, your next responsibility is to determine a time to seal the kettle to let in only that yeast. This is sometimes called isolating the yeast.

The reason for isolating yeasts is that when making beer, the brew is (or, at least, can be) affected by all of the microbes that go into it. Having mold, acetobacter, or lactobacilli affecting your brew could ruin it completely, and at the very least will siphon off sugar that could be used to make precious, precious alcohol. On the other hand, having two or more different yeasts coexist in a brew isn't necessarily bad -- very often, it's good and desirable -- but predicting the results of single-yeast brews is a lot simpler. So it's typical for many brewers to just work with one yeast at a time.

You isolate a yeast by running a Yeast Test. This kettle option is a shortcut that eliminates the brewing phase, thus taking only 40 minutes to complete. At the end of the test, you take the 'beer' (you need your small barrel!) and get a display of the results. At the bottom is a list of the microbes that are in the kettle, in the order they entered (first to last).

- Run a yeast test (The Yeast option, which takes 25 water, 60 wood, 2400 Teppy seconds (about 44.25 minutes real time)), leaving the lid open until the end. If the first microbe in the list is not a yeast, start over in another spot. Don't forget to have a small barrel with you so you can get the results of the yeast test!

- Once you find somewhere where at least the first microbe is a yeast, run a new yeast test, closing the lid at 1200 seconds (the halfway point of the fermentation phase).

- If the results show no microbes, it means you have closed the lid too soon; run a new test and close the lid at 600 seconds (remaining). If the results show more than one microbe, run another yeast test and close the lid at 1800 seconds to see if you have isolated the time when the first yeast enters the kettle.

- Keep running yeast tests, dividing the times when the yeast might have entered in half, until you get only the first yeast. This tells you your sealing time when making beer -- close the lid at the same time as you did in this successful test so that only this first yeast will be active in your beer.

Microbes appear to enter the kettle on seconds divisible by 12. It is possible for two or more microbes to enter simultaneously.

NOTE: If you are in a spot where the second (or more) microbes are also yeasts, you may also want to try making multi-yeast beer by finding the seal time that gets you only 2 yeasts (or 3, etc, up to however many you have). While the results of multiple-yeast brews are hard to predict, some people have successfully used the beerCalc tool to do this. Moreover, many beers made without sealing the lid are effectively multi-yeast beers, and you can find many such recipes and locations on the Wiki (do a search for your yeast -- e.g., search for Y3 to find pages with recipes for that yeast).

Microbe Transition Lines

Hellinar - Inspired by Jaby's work on large scale microbe distribution, I've been testing the changes in microbe distribution on small scales. These tests demonstrate that the microbe population shifts as your kettle crosses coordinate lines. The degree of shift is dependent on the degree to which the coordinate is divisible by two. Thus if the coordinate you cross is divisible by 128, most of the upper microbes will change. On the other hand if the coordinate can only be divided by 8, or 4 or 2, the shift in order is likely to be small. This shift occurs very sharply within a small fraction of a coordinate. So avoid placing kettles on such a high power of two coordinate. On the other hand, if you are searching for new microbes, place four kettles on odd numbered coordinates around the point where two lines divisible by 128 cross. This will give you four sets of well shuffled microbes.